“Did You Know”

Full access to the PGA Tour for Black golfers was a 28-year odyssey!

When the PGA of America was founded in 1916 there was a haphazard schedule of golf tournaments around the USA for white male golf professionals only. By 1930 the program had become organized into what was known as the PGA Tour.

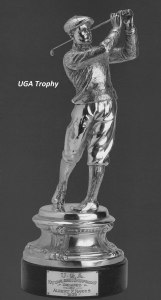

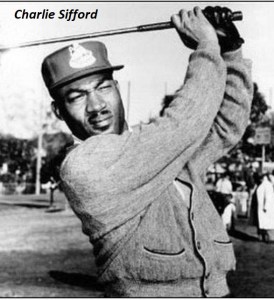

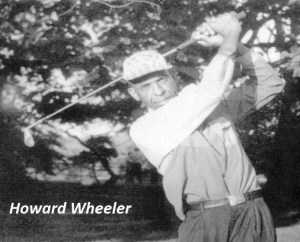

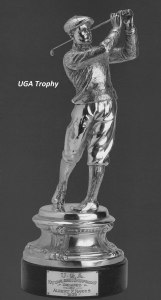

With no access to the white tournaments the Black golfers formed the United Golfers Association in the 1920s with a series of tournaments. They initiated a Negro National Open in 1926, which later had a trophy donated by Albert Harris, a Black Washington DC lawyer. Howard Wheeler and Charlie Sifford, two Black golf professionals who played out of Philadelphia’s Cobbs Creek Golf Club, each won the tournament six times.

In 1934 Chicago’s Robert “Pat” Ball, a Black golf professional, played in the PGA Tour’s St. Paul Open. He didn’t finish in the money, but he did have some decent scores that included a 72 in the second round. In September Ball won the 1934 Negro National Championship for a second time.

At its national meeting in November 1934 the PGA added a “Caucasians Only” clause to its constitution, concerning membership in its association.

In 1942 George S. May invited Black golfers to enter his tournament in Chicago, the Tam O’Shanter Open. The prior week seven Black golfers had been barred from playing in the Hale America Open, also held in Chicago. With a sponsor’s exemption, two-time Negro National Champion Howard Wheeler did not have to qualify for Tam O’Shanter. Six of the other Black entries, including Pat Ball, made it through Monday qualifying for the tournament. Three, including Wheeler, made the cut but didn’t finish in the money. An estimated 2,000 spectators followed the long driving Wheeler, who played with a cross-handed grip. In the following years Black golfers continued to play in PGA Tour events at Tam O’Shanter.

Howard Wheeler was allowed to attempt to qualify for the 1947 Philadelphia Inquirer Open, which he did with ease. He made the cut but missed the money. The tournament was in its fourth year, but this was the first time a Black golfer was given the opportunity to qualify in Philadelphia. The following year Wheeler qualified again for the Inquirer Open, once again making the cut and missing the money. Charlie Sifford, who like Wheeler played out of Cobbs Creek, made his first appearance in a PGA Tour event, qualifying and missing the cut.

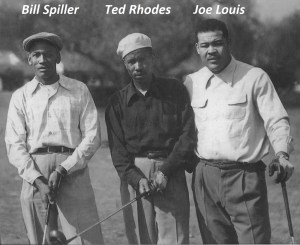

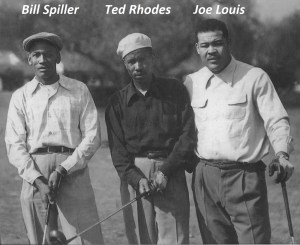

Beginning in 1945 the Los Angeles Open had begun to accept the entries from Black golfers. Ted Rhodes and Bill Spiller had some success, qualifying and making the cut several times.

Spiller, who had attended college and had a teaching certificate, had taught school in a rural Texas town for $60 a month. He moved to Los Angeles to work as a Red Cap at the Union Station (RR) where he could make more money. It was there that he took up golf in 1942 at age 29. Four years later he was beating nearly everyone. Twice he qualified for the Los Angeles Open as an amateur.

At the 1948 Los Angeles Open Ted Rhodes and Bill Spiller finished 23rd and 31st. The PGA Tour guidelines stated if a player finished in the top 60 at a PGA Tour tournament they were eligible to play in the next tournament, without having to qualify. Next up was the Bing Crosby Pro-Am. With 70 pros and 70 amateurs playing on one course, Cypress Point, there was no space for non exempt players who had been in the top 60 at L.A. Instead, their eligibility shifted to the next week’s Richmond (CA) Open.

Spiller and Rhodes filed entries for the Richmond Open and played a couple of practice rounds, only to be informed that they were not eligible to play, because they were not PGA “Approved Players”. Along with its members, the PGA had “Approved Players” cards for outstanding players who had turned pro but were not yet PGA members. They were all Caucasians.

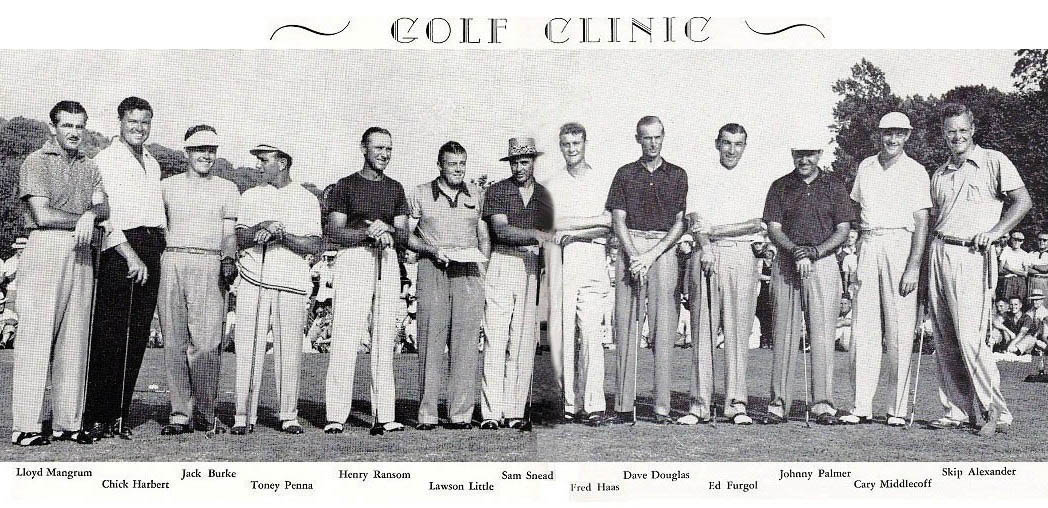

At that time the PGA had a “PGA Co-sponsored” contract which was presented to each tournament sponsor to sign. In signing that contract the sponsor paid the PGA $1,500 to run the tournament. The sponsor had to put the total purse dollars into an escrow account, which guaranteed the players would be paid. The PGA would run the tournament from beginning to end, including scoring and rules. Along with that, the PGA would stage a golf clinic on Wednesday afternoons where 12 or so players demonstrated golf shots for the fans. Some sponsors, like Tam O’Shanter or Los Angeles, didn’t sign the contract. They just told the PGA they would run the tournament on their own. Due to offering more prize money than most other tournaments, the PGA stepped aside.

Before the Richmond Open was completed a San Francisco lawyer had filed a $315,000 lawsuit against the PGA of America and the Richmond Golf Club on behalf of Rhodes and Spiller, who were not allowed to participate. The Richmond winner, Dutch Harrison, was issued a blank check because the law suit had frozen all funds.

Six weeks later PGA officials informed Spiller and Rhodes that something would be worked out for the future. They withdrew the lawsuit. Nothing changed. Then Spiller applied to the PGA for an “Approved Players” card. Two PGA members from California singed his application as sponsors. Three years later Spiller’s application was still being processed. To avoid any challenges some tournaments went as far as changing their names from Open to Invitation.

In 1952 after failing to qualify for the L.A. Open, Spiller and a Black amateur, Eural Clark, filed entries to the next full field PGA tournament, the San Diego Open. Due to a clerical error, they were assigned lockers and starting times for the qualifying rounds. With this tournament being PGA co-sponsored they were then denied the right to play. At the same time the San Diego sponsors had invited recently retired heavy weight boxing champion Joe Louis, who was Black and an amateur, to play in the tournament.

Under protest, Spiller and Clark played in the qualifying rounds. Spiller qualified. PGA President Horton Smith was in Pebble Beach playing in the Crosby Pro-Am. When contacted by the press, Smith stated he needed to confer with his PGA Executive Committee and would make a ruling when he arrived in San Diego.

When Smith arrived he held a meeting with his seven man PGA tournament committee. Spiller barged into the meeting and stated his case before being forced to exit. After a meeting that lasted two hours Smith ruled that Spiller couldn’t play. He said Spiller was not a PGA member or a PGA Tour “Approved Player”. Smith said that Louis could play, as an amateur did not fall under PGA by-laws. Spiller was quoted as saying “That Horton Smith, he can talk the paint off the wall.”

At first Louis refused to play saying the tournament should be called off. Louis stated that he would double the $2,000 that the tournament sponsors had promised a charity. Louis said, “This is the biggest fight of my life.” Louis, who had been sponsoring a tournament in Detroit for the Black golfers for several years, compared Horton Smith to Hitler.

Walter Winchell interviewed Louis on one of his radio broadcasts that was heard by 20 million people. Jackie Robinson sent a telegram to Louis stating his support. Louis agreed to play in the tournament, saying he hoped it might help the cause of Black golfers. When it was time for the first pairing to tee off in the tournament Spiller stood on the first tee refusing to let anyone tee off and making a statement. He was removed from the tee and play began. Some Black golfers called it the single most important event in their fight. Louis was criticized by some for agreeing to play when the other Black golfers were barred.

Before the tournament was over, Smith called another meeting of the tournament committee. After the meeting Smith announced an amendment to the PGA Tournament Regulations. It was called Approved Entries. The Sponsor already could invite 10 players who did not have to qualify to play. Now they could also invite ten from an Approved Entries list, which could be Black golfers, but they had to compete in Monday qualifying. Approved Entries participation was entirely up to the sponsor and the host course. A committee was created to screen Black golfers that could be Approved Entries. The chairman was Ted Rhodes with Joe Louis as co-chairman. The other three were Bill Spiller, Howard Wheeler and Eural Clark.

Smith went on record, saying the Caucasian Only clause would be critically analyzed at the PGA’s annual meeting in November with a view to modification or elimination. It probably was discussed, but it was not on the record. Everything stayed the same.

The following week at the Phoenix Open six Black golfers, including Joe Louis, were entered in the qualifying round. The six Black golfers were paired together in the first two groups off the tee. When the first group arrived on the first green and removed the flagstick to putt, they discovered the cup was filled with human excrement. There was a 30-minute delay for green keepers to clean up the mess and cut a new cup. Rhodes, Spiller, Clark and Sifford qualified. Rhodes made the cut. The PGA had kicked the can down the road. There was some opportunity for Black golfers, but limited, as it was only at northern venues or the west coast.

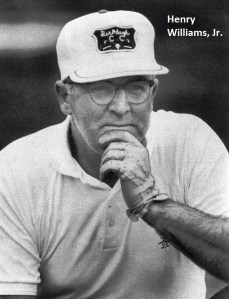

One week later, Joe Louis played in the Tucson Open and easily made the cut with a (69-72) 141. Frank Stranahan and Philadelphia’s Skee Riegel held the lead at the end of 36 holes at 132. Louis posted a 78 in the third round and pulled out of the tournament after nine holes of the final round. He had made a case for Black golfers competing in professional golf tournaments. Fleetwood Pennsylvania’s Henry William, Jr. won the tournament.

In 1955 and 1956 Black golf professionals played in the Philadelphia Daily News Open held at Cobbs Creek Golf Club. Charlie Sifford showed his capability, tying for sixth in 1956.

In 1960 it was announced that the 1962 PGA Championship would be held in Los Angeles. Spiller mentioned to someone that California Black golfers like Charlie Sifford could not play in the tournament. Sifford had played in the US Open that year and finished in the money. Spiller’s man contacted California attorney general Stanley Mosk and Mosk informed the PGA that its championship would not be held in California unless Sifford was in the tournament. To play in the tournament, Sifford as a non PGA member had to be in the top 25 money winners on the PGA Tour. With limited access to the PGA Tour, he wasn’t.

The Southern California PGA Section presented a resolution at the 1960 national meeting that would eliminate the Caucasian Only line from the PGA’s constitution. The resolution did not receive the required 2/3 vote to pass. The PGA moved its championship to Aronimink Golf Club in Philadelphia.

At the 1961 PGA meeting the PGA’s Board of Directors presented the same resolution to remove the Caucasian Only clause. It was seconded by several PGA Sections and passed 87 to 0. Twenty-seven years after the Caucasian Only clause was put into its constitution it was finally removed. Black golfers could now be PGA members with full privileges.

Robert “Pat” Ball, competing in the 1934 St. Paul Open, may be the reason why the PGA added the Caucasian Only clause to its constitution. Then it was Bill Spiller who worked the hardest and achieved the most success to overturn it. By the time it happened, Spiller’s window of opportunity had closed.

For more information on the history of the Black golf professionals, the three books listed below might be of interest to you.

Forbidden Fairways, by Calvin H. Sinnette, 1998

Just Let Me Play, by Charlie Sifford and James Gullo, 1992

Uneven Lies, by Pete McDaniel, 2000

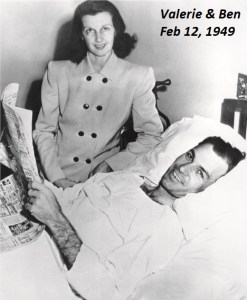

When the tournament began Hogan demanded that photographers not be allowed to take pictures of him during the round. He said cameras made him jumpy. Hogan felt that due to the circumstances more photographers would be following him than all the other players. The cameramen objected strenuously. Later Hogan agreed to be photographed, but only when he wasn’t playing a shot, which the photographers considered a ridicules request. A sign “No Cameras Please” traveled the golf course with Hogan.

When the tournament began Hogan demanded that photographers not be allowed to take pictures of him during the round. He said cameras made him jumpy. Hogan felt that due to the circumstances more photographers would be following him than all the other players. The cameramen objected strenuously. Later Hogan agreed to be photographed, but only when he wasn’t playing a shot, which the photographers considered a ridicules request. A sign “No Cameras Please” traveled the golf course with Hogan.

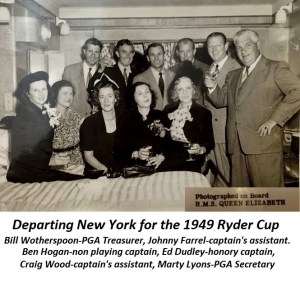

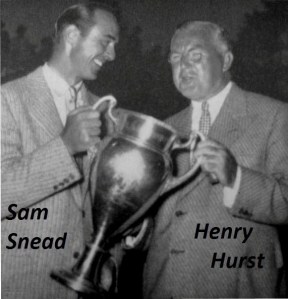

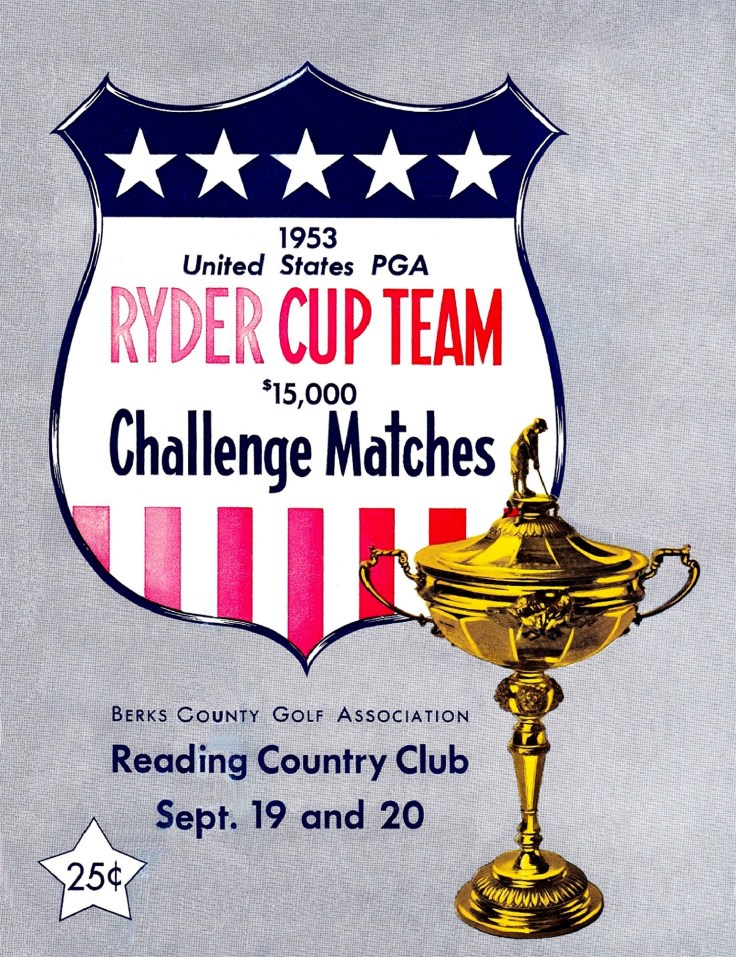

Snead was replaced as playing captain of the Ryder Cup team by Jerry Barber, who had won the PGA Championship that year. Barber had been the professional at Cedarbrook Country Club in 1950 and won the Pennsylvania Open that year. Wilmington, DE’s Ed “Porky” Oliver, who was in poor health, had been named honorary captain by the PGA, but died before the Ryder Cup was played.

Snead was replaced as playing captain of the Ryder Cup team by Jerry Barber, who had won the PGA Championship that year. Barber had been the professional at Cedarbrook Country Club in 1950 and won the Pennsylvania Open that year. Wilmington, DE’s Ed “Porky” Oliver, who was in poor health, had been named honorary captain by the PGA, but died before the Ryder Cup was played.

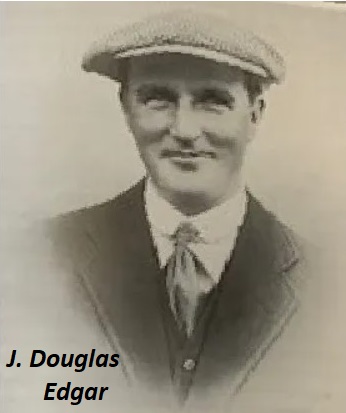

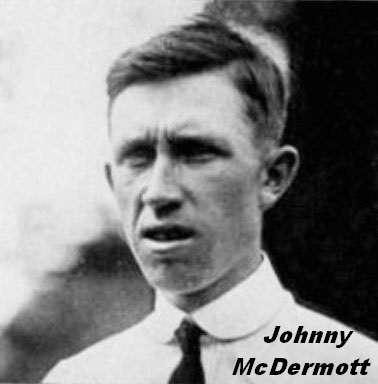

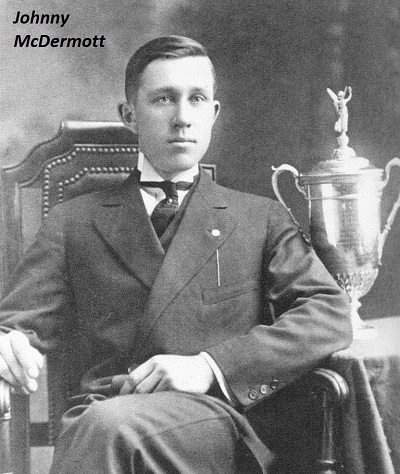

Three homebred American professionals–Johnny McDermott, Tom McNamara and Mike Brady, were selected, with one more to be decided. While there, they would play in The Open before heading to France for the challenge match. Later, Alex Smith, a transplanted Scottish professional who was the professional at Wykagyl CC in Westchester County, New York, was chosen to fill out the four-man team. McDermott and Smith had won the last three US Opens.

Three homebred American professionals–Johnny McDermott, Tom McNamara and Mike Brady, were selected, with one more to be decided. While there, they would play in The Open before heading to France for the challenge match. Later, Alex Smith, a transplanted Scottish professional who was the professional at Wykagyl CC in Westchester County, New York, was chosen to fill out the four-man team. McDermott and Smith had won the last three US Opens.  The Open was played at Royal Liverpool Golf Club with 36 holes a day for two days. On Sunday, the day before the start of the competition, the golf course was closed to all play. The weather had been unusually hot and the forecast was good. Then during the tournament on Monday and Tuesday, June 23 and 24, the weather was about as bad as it could be. On the first day the greens were flooded from rain that began during the night and continued throughout the day. The second day presented gale force winds and drenching rain at times. McDermott had his moments. An opening round 75 was just two strokes off the lead, but an afternoon 80 set him back. On the second day McDermott was one under fours for the first seven holes and after nine holes only three strokes off the lead. But, with problems on the second nine his total for the round was 77. With a final round 83 McDermott tied for fifth, winning seven pounds and ten shillings. With a compact swing, J.H. Taylor had the right golf game for the elements. His 304 total made him the winner of The Open for a fifth time, this one by eight strokes. But, if not for having holed a six-foot putt on the final green of qualifying, Taylor would not have even been in the tournament.

The Open was played at Royal Liverpool Golf Club with 36 holes a day for two days. On Sunday, the day before the start of the competition, the golf course was closed to all play. The weather had been unusually hot and the forecast was good. Then during the tournament on Monday and Tuesday, June 23 and 24, the weather was about as bad as it could be. On the first day the greens were flooded from rain that began during the night and continued throughout the day. The second day presented gale force winds and drenching rain at times. McDermott had his moments. An opening round 75 was just two strokes off the lead, but an afternoon 80 set him back. On the second day McDermott was one under fours for the first seven holes and after nine holes only three strokes off the lead. But, with problems on the second nine his total for the round was 77. With a final round 83 McDermott tied for fifth, winning seven pounds and ten shillings. With a compact swing, J.H. Taylor had the right golf game for the elements. His 304 total made him the winner of The Open for a fifth time, this one by eight strokes. But, if not for having holed a six-foot putt on the final green of qualifying, Taylor would not have even been in the tournament.

The grip wasn’t a new idea, but very few golfers used it. Two great golfers, Gene Sarazen and Jock Hutchison, played with that grip throughout their entire careers.

The grip wasn’t a new idea, but very few golfers used it. Two great golfers, Gene Sarazen and Jock Hutchison, played with that grip throughout their entire careers.

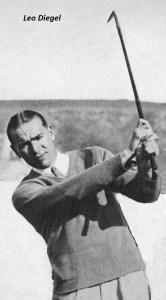

The 1924 Shawnee Open kicked off three days after the Metropolitan Open ended in New York. Again, it was scheduled for 72 holes in two days. The players got a break as the high temperature in the Poconos for the two days was in the low 70’s. In a tightly contested tournament, Joe Kirkwood, who was living in Glenside, Pennsylvania and a member at Cedarbrook Country Club, led the first day, at 143. The second day Detroit’s Leo Diegel and Chicago’s Willie Macfarlane ended up in a tie for first at nine under par 287. As in 1923, the tournament officials sent them back out for an 18-hole playoff. Macfarlane said it wasn’t fair as Diegel was the best twilight golfer in the world. That seemed to be the case. With the sun sinking fast, Diegel put together a 69, which equaled the low round of the tournament, against a 76 for Macfarlane. Kirkwood finished third, one stroke out of the playoff. First prize was $500. In the late 1920s Diegel won the PGA Championship two years in a row, and later was the professional at Philmont Country Club.

The 1924 Shawnee Open kicked off three days after the Metropolitan Open ended in New York. Again, it was scheduled for 72 holes in two days. The players got a break as the high temperature in the Poconos for the two days was in the low 70’s. In a tightly contested tournament, Joe Kirkwood, who was living in Glenside, Pennsylvania and a member at Cedarbrook Country Club, led the first day, at 143. The second day Detroit’s Leo Diegel and Chicago’s Willie Macfarlane ended up in a tie for first at nine under par 287. As in 1923, the tournament officials sent them back out for an 18-hole playoff. Macfarlane said it wasn’t fair as Diegel was the best twilight golfer in the world. That seemed to be the case. With the sun sinking fast, Diegel put together a 69, which equaled the low round of the tournament, against a 76 for Macfarlane. Kirkwood finished third, one stroke out of the playoff. First prize was $500. In the late 1920s Diegel won the PGA Championship two years in a row, and later was the professional at Philmont Country Club.

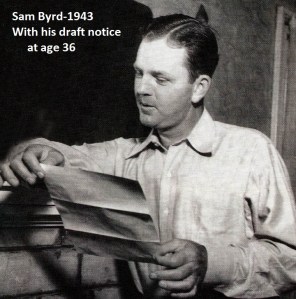

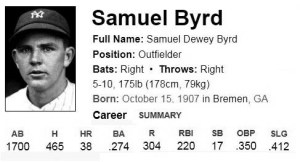

Byrd had been a former major league baseball outfielder for eight years and a backup to Babe Ruth with the New York Yankees. When Ruth was traded to the Boston Braves Byrd turned to golf. He was a teaching pro at Philadelphia Country Club for three years (1937-39) and at Merion Golf Club for four years (1940-43). In early 1943 Byrd received a letter from his Draft Board to report for a physical. He was 36 and would be 37 before the year was over. He was not drafted. Now he was the head professional at a club in Detroit.

Byrd had been a former major league baseball outfielder for eight years and a backup to Babe Ruth with the New York Yankees. When Ruth was traded to the Boston Braves Byrd turned to golf. He was a teaching pro at Philadelphia Country Club for three years (1937-39) and at Merion Golf Club for four years (1940-43). In early 1943 Byrd received a letter from his Draft Board to report for a physical. He was 36 and would be 37 before the year was over. He was not drafted. Now he was the head professional at a club in Detroit.

In the south, college football in early November came before golf, even an international golf match, so the Ryder Cup was scheduled for Friday and Sunday. On Friday the US team won 3 of the possible 4 points in the foursomes (alternate strokes) matches. On Saturday the golf professionals attended the University of North Carolina/University of Tennessee football game, as guests of UNC. Number one raked Tennessee won 27-0.

In the south, college football in early November came before golf, even an international golf match, so the Ryder Cup was scheduled for Friday and Sunday. On Friday the US team won 3 of the possible 4 points in the foursomes (alternate strokes) matches. On Saturday the golf professionals attended the University of North Carolina/University of Tennessee football game, as guests of UNC. Number one raked Tennessee won 27-0.

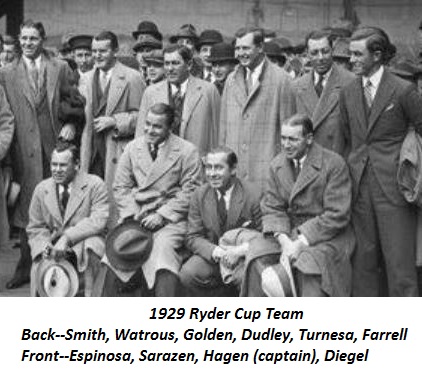

In 1931 it was now official, team members had to be born in the country they represented. Along with that, they had to be domiciled in the country they represented. The British PGA thought that two-time PGA champion Leo Diegel should not be eligible. Diegel was employed in Agua Caliente, Mexico, but when he showed that he had an apartment in San Diego 21 miles away, he was allowed to play. Three GB professionals who been on the victorious 1929 team were out. Two were working as club professionals across the English Channel on the mainland of Europe. Their best player, Henry Cotton, pulled out refusing to equally split any exhibition money he and the team members might earn while in the states. Cotton attended the Ryder Cup, working for a British newspaper. When Hagen held tryouts at Scioto CC, the host club, a US professional who played in the first two Ryder Cups failed to show, saying he was too busy at his club. It was thought that he might not have been born in the states. The US won 9-3.

In 1931 it was now official, team members had to be born in the country they represented. Along with that, they had to be domiciled in the country they represented. The British PGA thought that two-time PGA champion Leo Diegel should not be eligible. Diegel was employed in Agua Caliente, Mexico, but when he showed that he had an apartment in San Diego 21 miles away, he was allowed to play. Three GB professionals who been on the victorious 1929 team were out. Two were working as club professionals across the English Channel on the mainland of Europe. Their best player, Henry Cotton, pulled out refusing to equally split any exhibition money he and the team members might earn while in the states. Cotton attended the Ryder Cup, working for a British newspaper. When Hagen held tryouts at Scioto CC, the host club, a US professional who played in the first two Ryder Cups failed to show, saying he was too busy at his club. It was thought that he might not have been born in the states. The US won 9-3.

Coburn Haskell, a Cleveland businessman, now known as the inventor of the modern golf ball, was visiting the Goodyear Rubber Company in Akron, Ohio in 1898. Seeing some strips of rubber he began winding them around a ball. When dropped on the floor it bounced back up. That gave him an idea. With the assistance of the Goodyear Company, Haskell formed a business manufacturing golf balls. The “Haskell golf ball” revolutionized the golf ball. The Haskell ball went 20 yards farther than the Guttie, making many of the golf courses 500 yards too short and obsolete. The first Haskell ball was somewhat difficult to control. Some named it the “Bounding Billie”. Haskell made several improvements to the original ball, like improving the cover.

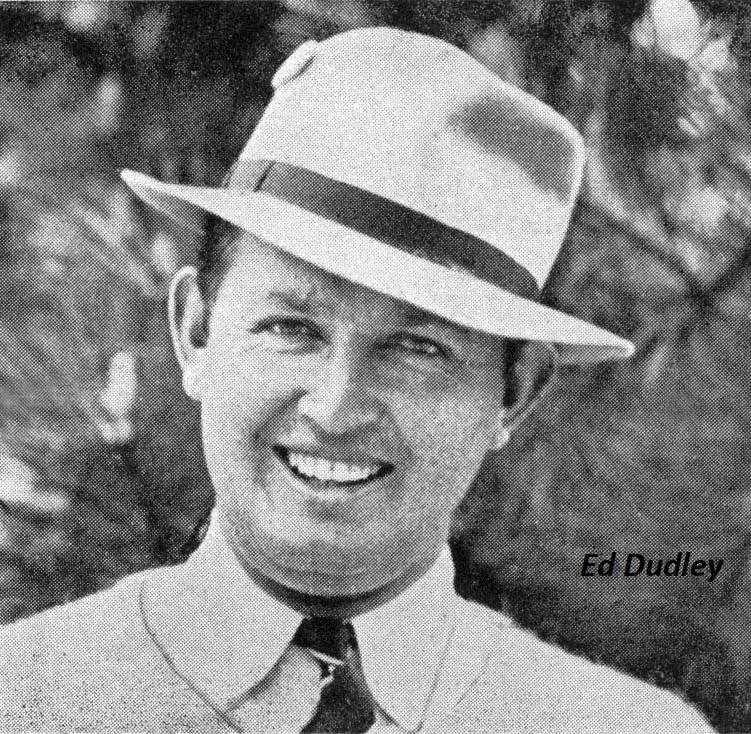

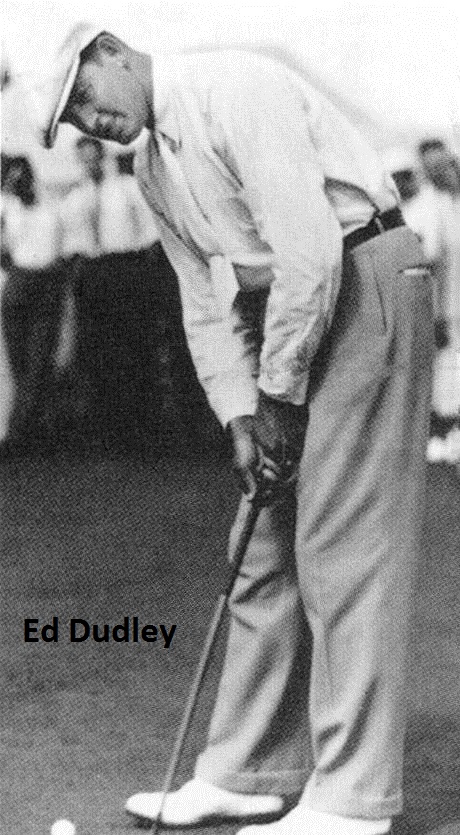

Coburn Haskell, a Cleveland businessman, now known as the inventor of the modern golf ball, was visiting the Goodyear Rubber Company in Akron, Ohio in 1898. Seeing some strips of rubber he began winding them around a ball. When dropped on the floor it bounced back up. That gave him an idea. With the assistance of the Goodyear Company, Haskell formed a business manufacturing golf balls. The “Haskell golf ball” revolutionized the golf ball. The Haskell ball went 20 yards farther than the Guttie, making many of the golf courses 500 yards too short and obsolete. The first Haskell ball was somewhat difficult to control. Some named it the “Bounding Billie”. Haskell made several improvements to the original ball, like improving the cover.  Ed Dudley, in his third year as the professional at the Concord Country Club south of Philadelphia, found the ball to his liking. He won the Los Angeles Open and the Western Open along with compiling the lowest scoring average on the PGA Tour for 1931. Most golfers didn’t like the ball. The lighter ball was difficult to control in the wind. Also at times the light ball would not stay in place on the greens when it was windy. Some frustrated golfers referred to it as the “Balloon Ball”.

Ed Dudley, in his third year as the professional at the Concord Country Club south of Philadelphia, found the ball to his liking. He won the Los Angeles Open and the Western Open along with compiling the lowest scoring average on the PGA Tour for 1931. Most golfers didn’t like the ball. The lighter ball was difficult to control in the wind. Also at times the light ball would not stay in place on the greens when it was windy. Some frustrated golfers referred to it as the “Balloon Ball”.

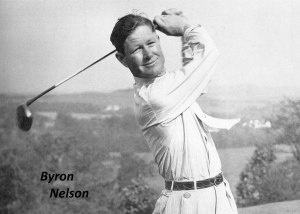

1937 was a Ryder Cup year, with Great Britain being the host. The final four spots on the US team were determined from the two qualifying rounds at the PGA Championship and the US Open’s four rounds. As the medalist at the PGA, and a tie for 20th at the US Open in Detroit, Nelson earned one of those last spots.

1937 was a Ryder Cup year, with Great Britain being the host. The final four spots on the US team were determined from the two qualifying rounds at the PGA Championship and the US Open’s four rounds. As the medalist at the PGA, and a tie for 20th at the US Open in Detroit, Nelson earned one of those last spots.

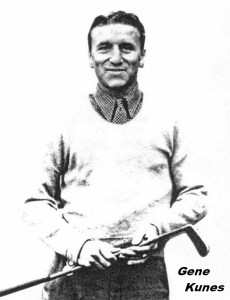

At Montreal Kunes was on his game, outplaying a strong field which included Walter Hagen, Paul Runyan and Horton Smith. Kunes won by two strokes as he put together rounds of 70-68-74-68 for an even par 280. Vic Ghezzi finished second at 282. Tony Manero and Dudley tied for third with 285 totals.

At Montreal Kunes was on his game, outplaying a strong field which included Walter Hagen, Paul Runyan and Horton Smith. Kunes won by two strokes as he put together rounds of 70-68-74-68 for an even par 280. Vic Ghezzi finished second at 282. Tony Manero and Dudley tied for third with 285 totals.

When the Jeffersonville Golf Club in Norristown, Pennsylvania, another Ross design, opened for play in 1931, Ross paved the way for Wood to be the professional there. Born in Canada to French Canadian parents in 1902, Wood’s family moved to the states when he was a young boy. Born Francois Dubois, his name was Americanized to Frank Wood.

When the Jeffersonville Golf Club in Norristown, Pennsylvania, another Ross design, opened for play in 1931, Ross paved the way for Wood to be the professional there. Born in Canada to French Canadian parents in 1902, Wood’s family moved to the states when he was a young boy. Born Francois Dubois, his name was Americanized to Frank Wood.

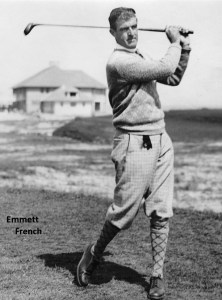

By 1908 he was an assistant pro at the club. In 1913, one year after Merion opened its famous East Course, French left Merion to become the professional at the Country Club of York. At York his golf game began to show signs of greatness. In 1919 he finished second to Walter Hagen at the Met Open, lost in the quarter final of PGA Championship to Jim Barnes the winner, finished third at the Shawnee Open and won the Philadelphia Open which was open to all comers. At the end of the year he was ranked eighth in the United States.

By 1908 he was an assistant pro at the club. In 1913, one year after Merion opened its famous East Course, French left Merion to become the professional at the Country Club of York. At York his golf game began to show signs of greatness. In 1919 he finished second to Walter Hagen at the Met Open, lost in the quarter final of PGA Championship to Jim Barnes the winner, finished third at the Shawnee Open and won the Philadelphia Open which was open to all comers. At the end of the year he was ranked eighth in the United States.

Thursday the wind died down and Pittsburgh’s Allegheny CC professional, Jock Hutchison, took the lead at 149. In Friday’s 36-hole finish, Hutchison put together rounds of 71 and 72. His 292 total won by 7 strokes. Boston’s Tom McNamara, who was national sales manager for Wanamaker’s golf division, finished second at 299.

Thursday the wind died down and Pittsburgh’s Allegheny CC professional, Jock Hutchison, took the lead at 149. In Friday’s 36-hole finish, Hutchison put together rounds of 71 and 72. His 292 total won by 7 strokes. Boston’s Tom McNamara, who was national sales manager for Wanamaker’s golf division, finished second at 299. Perrin was only president of the USGA that one year. When the US Open resumed in 1919 after WWI, it was played at Brae Burn and the winner was Hagen.

Perrin was only president of the USGA that one year. When the US Open resumed in 1919 after WWI, it was played at Brae Burn and the winner was Hagen.

On Friday 73 professionals and amateurs teed off in the first round. Sam Snead took the lead with a course record 64 for the 6,397 yard course. Despite a second round 74 Snead was still in the lead, but tied. On Sunday morning Snead posted a 69 to lead by 5 and then an afternoon 65 ended all doubt. His 272 total won by nine strokes. Dick Metz (281) was second and Demaret (282) was third. First prize was $1,500, as 12 professionals shared the $5,000.

On Friday 73 professionals and amateurs teed off in the first round. Sam Snead took the lead with a course record 64 for the 6,397 yard course. Despite a second round 74 Snead was still in the lead, but tied. On Sunday morning Snead posted a 69 to lead by 5 and then an afternoon 65 ended all doubt. His 272 total won by nine strokes. Dick Metz (281) was second and Demaret (282) was third. First prize was $1,500, as 12 professionals shared the $5,000.

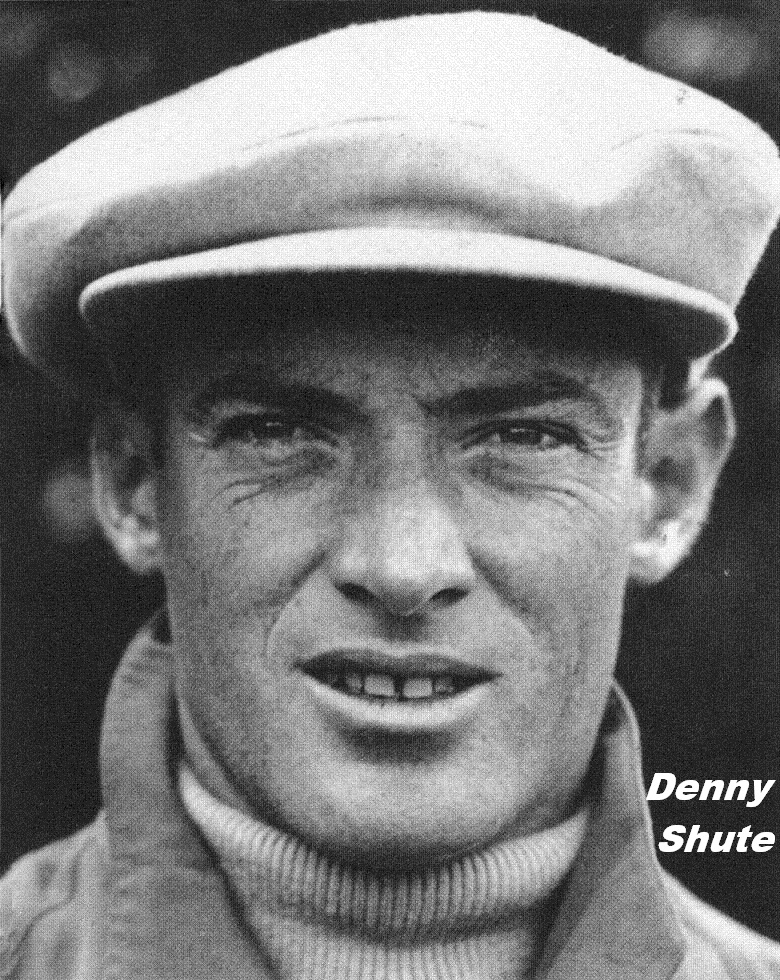

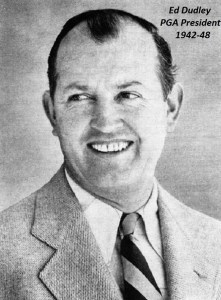

When the other professionals entered in the tournament heard the results of the vote, 51 prominent tournament players signed a petition stating that they would not play unless Shute’s entry was accepted. A Pomonok member, Corky O’Keefe, who had put up $15,000 to sponsor the tournament, threatened a lawsuit against the PGA and Pomonok, stating there would not be a tournament unless Shute was playing. More meetings of the PGA executive committee were held. Philadelphia CC professional Ed Dudley, who was the PGA Tour tournament chairman and a national vice president, was in favor of Shute playing.

When the other professionals entered in the tournament heard the results of the vote, 51 prominent tournament players signed a petition stating that they would not play unless Shute’s entry was accepted. A Pomonok member, Corky O’Keefe, who had put up $15,000 to sponsor the tournament, threatened a lawsuit against the PGA and Pomonok, stating there would not be a tournament unless Shute was playing. More meetings of the PGA executive committee were held. Philadelphia CC professional Ed Dudley, who was the PGA Tour tournament chairman and a national vice president, was in favor of Shute playing.

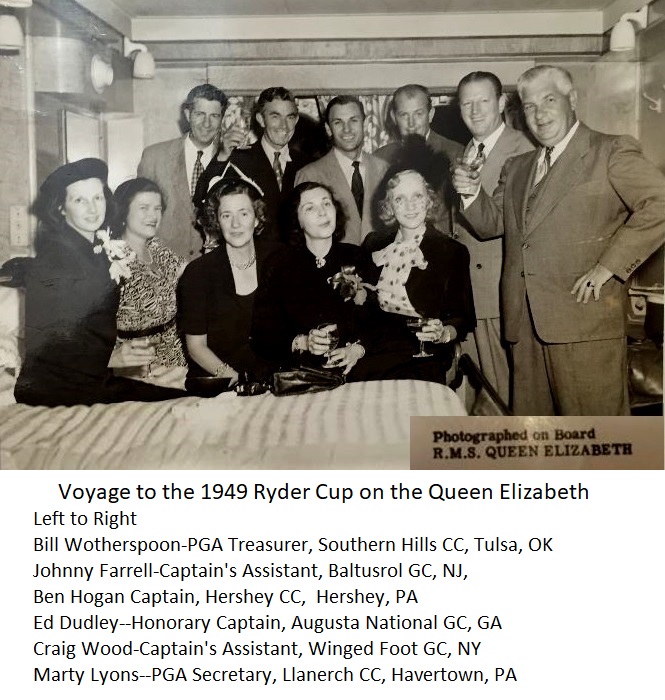

On Monday and Tuesday, the hopeful professionals played 36 holes each day. At the conclusion Billy Burke led with a one over par 289. (Bobby Jones had won the 1926 US Open at Scioto with a 293) Wiffy Cox (294) was next and Craig Wood (299) picked up the third place. Denny Shute, who would be the professional at Llanerch Country Club two years later, tied Frank Walsh and Henry Cuici for the fourth and last spot with 302 totals. On Wednesday they played an 18-hole playoff which Shute won with a 72. Dudley, who had been on the team the previous year, missed the playoff by one stroke with a 303 total.

On Monday and Tuesday, the hopeful professionals played 36 holes each day. At the conclusion Billy Burke led with a one over par 289. (Bobby Jones had won the 1926 US Open at Scioto with a 293) Wiffy Cox (294) was next and Craig Wood (299) picked up the third place. Denny Shute, who would be the professional at Llanerch Country Club two years later, tied Frank Walsh and Henry Cuici for the fourth and last spot with 302 totals. On Wednesday they played an 18-hole playoff which Shute won with a 72. Dudley, who had been on the team the previous year, missed the playoff by one stroke with a 303 total.

In May of 1957 the Philadelphia Inquirer reported that the officials of the Atlantic City Country Club had been practically assured that the 1959 Ryder Cup would be played at their club. In November, at the PGA’s national meeting it was announced that Atlantic City CC would be hosting the Ryder Cup in 1959. The club and its pro-owner Leo Fraser would be sponsoring the match. In December, an article in the Inquirer mentioned that new championship tees were being built at Atlantic City CC for the Ryder Cup, adding 400 yards to the course. As late as August of 1958, news articles were still mentioning the upcoming Ryder Cup at Atlantic City.

In May of 1957 the Philadelphia Inquirer reported that the officials of the Atlantic City Country Club had been practically assured that the 1959 Ryder Cup would be played at their club. In November, at the PGA’s national meeting it was announced that Atlantic City CC would be hosting the Ryder Cup in 1959. The club and its pro-owner Leo Fraser would be sponsoring the match. In December, an article in the Inquirer mentioned that new championship tees were being built at Atlantic City CC for the Ryder Cup, adding 400 yards to the course. As late as August of 1958, news articles were still mentioning the upcoming Ryder Cup at Atlantic City.

In late 1934 the Yankees released the aging Ruth. They were bringing Joe DiMaggio up from the Pacific Coast League. After six seasons with the Yankees, Byrd was no longer needed. He was sold to the Cincinnati Reds, where he played two years before being traded to the St. Louis Cardinals. That is when he decided to leave baseball and concentrate on golf. His batting average for his eight major league seasons was .274. Baseball historians later wrote that Byrd’s baseball career was wasted sitting on the Yankees bench during his prime years.

In late 1934 the Yankees released the aging Ruth. They were bringing Joe DiMaggio up from the Pacific Coast League. After six seasons with the Yankees, Byrd was no longer needed. He was sold to the Cincinnati Reds, where he played two years before being traded to the St. Louis Cardinals. That is when he decided to leave baseball and concentrate on golf. His batting average for his eight major league seasons was .274. Baseball historians later wrote that Byrd’s baseball career was wasted sitting on the Yankees bench during his prime years.

George, Jr. became the head professional at Plymouth Country Club in 1936 and the next year he was the assistant at the Manufacturers Golf & CC, but those jobs were probably too much like work for him. He was good enough to be able to make a few dollars playing golf and for the next few years he assisted his father with a driving range in Jenkintown. He qualified for the 1931 PGA Championship and two US Opens. After that he spent his down time in Clearwater, Florida while playing the PGA Tour off and on.

George, Jr. became the head professional at Plymouth Country Club in 1936 and the next year he was the assistant at the Manufacturers Golf & CC, but those jobs were probably too much like work for him. He was good enough to be able to make a few dollars playing golf and for the next few years he assisted his father with a driving range in Jenkintown. He qualified for the 1931 PGA Championship and two US Opens. After that he spent his down time in Clearwater, Florida while playing the PGA Tour off and on. In a practice round before the 1962 PGA Championship at Aronimink, Nicklaus, on leaving the 11th tee, summoned George who had been resting next to a shade tree. George took Nicklaus’ putter and massaged the shaft on the tree, gave the shaft an eyeball inspection and handed it back to Nicklaus. In the mid 70’s he was quoted as saying that he was spending $50,000 a year of other people’s money. He said that he didn’t want to be too specific about his income, since the best line of defense with the IRS was a little discretion.

In a practice round before the 1962 PGA Championship at Aronimink, Nicklaus, on leaving the 11th tee, summoned George who had been resting next to a shade tree. George took Nicklaus’ putter and massaged the shaft on the tree, gave the shaft an eyeball inspection and handed it back to Nicklaus. In the mid 70’s he was quoted as saying that he was spending $50,000 a year of other people’s money. He said that he didn’t want to be too specific about his income, since the best line of defense with the IRS was a little discretion.

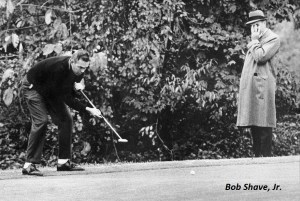

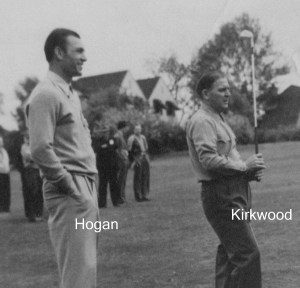

In 1941 the Philadelphia PGA held its second annual Golf Week. To promote golf, Section president Ed Dudley, Leo Diegel and other Section members played exhibitions and staged golf clinics at numerous locations. One of those exhibitions was held at the Langhorne Country Club on Saturday May 10. The host professional Al MacDonald and Jimmy Thomson, the longest driver in professional golf, took on Kirkwood and Ben Hogan, who was in his first year as the professional at the Hershey Country Club. Hogan, who was not known for watching others hit golf shots, can be seen in the photograph watching Kirkwood warm up.

In 1941 the Philadelphia PGA held its second annual Golf Week. To promote golf, Section president Ed Dudley, Leo Diegel and other Section members played exhibitions and staged golf clinics at numerous locations. One of those exhibitions was held at the Langhorne Country Club on Saturday May 10. The host professional Al MacDonald and Jimmy Thomson, the longest driver in professional golf, took on Kirkwood and Ben Hogan, who was in his first year as the professional at the Hershey Country Club. Hogan, who was not known for watching others hit golf shots, can be seen in the photograph watching Kirkwood warm up.

The PGA of America’s national meeting was held in Chicago in the middle of November. Ben Hogan, who was the professional at the Hershey Country Club, while playing a full schedule on the PGA Tour, made an unannounced appearance at the meeting. Hogan, the leader of an unofficial players group met with the PGA Executive Committee the day after the meeting ended. He presented a proposal for establishment of a seven-man player constituted board. The board would arrange schedules, control the PGA Tournament Bureau and punish absenteeism. A date was set to meet with Hogan’s committee later in the month at the Orlando Open. PGA President Ed Dudley, who had been a tour player, stated that Hogan’s committee and the PGA were both working toward the same objectives.

The PGA of America’s national meeting was held in Chicago in the middle of November. Ben Hogan, who was the professional at the Hershey Country Club, while playing a full schedule on the PGA Tour, made an unannounced appearance at the meeting. Hogan, the leader of an unofficial players group met with the PGA Executive Committee the day after the meeting ended. He presented a proposal for establishment of a seven-man player constituted board. The board would arrange schedules, control the PGA Tournament Bureau and punish absenteeism. A date was set to meet with Hogan’s committee later in the month at the Orlando Open. PGA President Ed Dudley, who had been a tour player, stated that Hogan’s committee and the PGA were both working toward the same objectives.

In 1949 Henry made it to the quarter-finals of the PGA Championship, and won the Philadelphia PGA Championship. By being a quarterfinalist in the PGA he earned an invite to the 1950 Masters Tournament. That year he went all the way to the final of the PGA, losing to Chandler Harper. With that he qualified for the Masters again.

In 1949 Henry made it to the quarter-finals of the PGA Championship, and won the Philadelphia PGA Championship. By being a quarterfinalist in the PGA he earned an invite to the 1950 Masters Tournament. That year he went all the way to the final of the PGA, losing to Chandler Harper. With that he qualified for the Masters again.

One day in the 1970s a man named Chet Harrington, who played golf, was in a trophy store in Philadelphia. He saw a dusty golf trophy on a shelf high up behind the counter. The clerk took it down from the shelf for him, saying that he was not sure what it was for. Having heard of Howard Wheeler, one of the names on the trophy, he bought it, cleaned it up and stored it in a bank vault for 35 years.

One day in the 1970s a man named Chet Harrington, who played golf, was in a trophy store in Philadelphia. He saw a dusty golf trophy on a shelf high up behind the counter. The clerk took it down from the shelf for him, saying that he was not sure what it was for. Having heard of Howard Wheeler, one of the names on the trophy, he bought it, cleaned it up and stored it in a bank vault for 35 years.

Two thousand spectators turned out that day, with the proceeds coming to $3,000. The plan had been to purchase an ambulance for the Red Cross, but the Red Cross officials suggested that the golf professionals visit the Valley Forge General Hospital near Phoenixville where the wounded service men were being sent for rehabilitation. Lyons and Diegel visited the hospital and decided to build a golf course for the hospital’s patients. More exhibitions and pro-ams were played to raise money and with the assistance of the Philadelphia Golf Course Superintendents, a nine-hole golf course consisting of holes from 95 yards to 275 was constructed. Every golf professional in the Philadelphia PGA gave his time, equipment or money to the project and many donated all three.

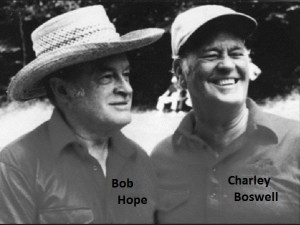

Two thousand spectators turned out that day, with the proceeds coming to $3,000. The plan had been to purchase an ambulance for the Red Cross, but the Red Cross officials suggested that the golf professionals visit the Valley Forge General Hospital near Phoenixville where the wounded service men were being sent for rehabilitation. Lyons and Diegel visited the hospital and decided to build a golf course for the hospital’s patients. More exhibitions and pro-ams were played to raise money and with the assistance of the Philadelphia Golf Course Superintendents, a nine-hole golf course consisting of holes from 95 yards to 275 was constructed. Every golf professional in the Philadelphia PGA gave his time, equipment or money to the project and many donated all three. In 1946 Boswell finished second in the National Blind Golf Championship and the next year he won the tournament. He went on to win the U.S. championship 16 times and the international title 11 times. He played golf with celebrities like Bob Hope.

In 1946 Boswell finished second in the National Blind Golf Championship and the next year he won the tournament. He went on to win the U.S. championship 16 times and the international title 11 times. He played golf with celebrities like Bob Hope.

One year earlier, Babe Zaharias had asked Besselink to be her partner in the 1952 International Mixed Two Ball Open in Orlando, which they had won. Having recently heard that Zaharias had been diagnosed with cancer, Besselink donated half his first prize, $5,000, to the Damon Runyan Cancer Fund.

One year earlier, Babe Zaharias had asked Besselink to be her partner in the 1952 International Mixed Two Ball Open in Orlando, which they had won. Having recently heard that Zaharias had been diagnosed with cancer, Besselink donated half his first prize, $5,000, to the Damon Runyan Cancer Fund.

The tournament committee decreed an 18-hole playoff that same day was in order. In those days most important tournament ties were settled with 18-hole playoffs and on occasion they were 36 holes. The 1931 U.S. Open took two 36-hole playoffs to determine a winner. Nowadays anything more than 18 in one day is considered quite a challenge. The players caught a break as the high temperatures in the Poconos, for the two days, was in the low 70s.

The tournament committee decreed an 18-hole playoff that same day was in order. In those days most important tournament ties were settled with 18-hole playoffs and on occasion they were 36 holes. The 1931 U.S. Open took two 36-hole playoffs to determine a winner. Nowadays anything more than 18 in one day is considered quite a challenge. The players caught a break as the high temperatures in the Poconos, for the two days, was in the low 70s.

The first two matches were 18 holes and the four after that were 36-hole matches. After seven days and 180 scheduled holes, Reading Country Club’s Byron Nelson and Hershey Country Club’s Henry Picard were in the final. At the end of 18 holes the match was even. In the afternoon there was a steady pelting rain, but it did not seem to bother Nelson who prevailed by the margin of 5&4. First prize was $3,000 which was double what Nelson had won at Augusta in April and Picard picked up a check for $2,000.

The first two matches were 18 holes and the four after that were 36-hole matches. After seven days and 180 scheduled holes, Reading Country Club’s Byron Nelson and Hershey Country Club’s Henry Picard were in the final. At the end of 18 holes the match was even. In the afternoon there was a steady pelting rain, but it did not seem to bother Nelson who prevailed by the margin of 5&4. First prize was $3,000 which was double what Nelson had won at Augusta in April and Picard picked up a check for $2,000.

Johnny McDermott, Morrie Talman and Frank Sprogell all grew up on the same city block in West Philadelphia and were within a few years of each other in age. They were introduced to golf as caddies at the Aronimink Golf Club, which was then located near where they lived. McDermott went on to win back to back US Opens and Talman became the head professional at the Whitemarsh Valley Country Club where he held forth for 40 years.

Johnny McDermott, Morrie Talman and Frank Sprogell all grew up on the same city block in West Philadelphia and were within a few years of each other in age. They were introduced to golf as caddies at the Aronimink Golf Club, which was then located near where they lived. McDermott went on to win back to back US Opens and Talman became the head professional at the Whitemarsh Valley Country Club where he held forth for 40 years.

When the war ended, Skee rose to the top of amateur golf. In the 1946 US Amateur, which was played at Baltusrol Golf Club, he qualified for the match play with a score of 136, which set a record that stood for more than 30 years. The next year he won the US Amateur at Pebble Beach. He won the 1948 Western Amateur and the Trans-Mississippi Amateur in 1946 and 1948. As a member of the 1947 and 1949 Walker Cup teams, he never lost a match.

When the war ended, Skee rose to the top of amateur golf. In the 1946 US Amateur, which was played at Baltusrol Golf Club, he qualified for the match play with a score of 136, which set a record that stood for more than 30 years. The next year he won the US Amateur at Pebble Beach. He won the 1948 Western Amateur and the Trans-Mississippi Amateur in 1946 and 1948. As a member of the 1947 and 1949 Walker Cup teams, he never lost a match.

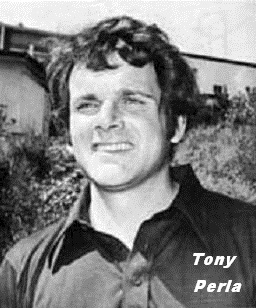

Gary Player and Don January tested the shafts. Thomas introduced the graphite shaft at the 1970 PGA Merchandise Show. Tony Perla, professional at Sunnybrook Golf Club and a two-time winner of the Pennsylvania Open, became Thomas’ local test pilot for the graphite shaft. Perla, the longest driver in the Philadelphia Section, was the perfect test for the shaft. With his power any flaws in the shaft were obvious.

Gary Player and Don January tested the shafts. Thomas introduced the graphite shaft at the 1970 PGA Merchandise Show. Tony Perla, professional at Sunnybrook Golf Club and a two-time winner of the Pennsylvania Open, became Thomas’ local test pilot for the graphite shaft. Perla, the longest driver in the Philadelphia Section, was the perfect test for the shaft. With his power any flaws in the shaft were obvious.

East Falls’ most famous golfer was Jack Burke, Sr. who worked at several Philadelphia clubs before moving west. Burke missed winning the 1920 U.S. Open by one stroke while working at the Town & Country Club in St. Paul, Minnesota. He went on to win the Senior PGA Championship in 1941. His son Jack Burke, Jr. won a PGA Championship and a Masters Tournament.

East Falls’ most famous golfer was Jack Burke, Sr. who worked at several Philadelphia clubs before moving west. Burke missed winning the 1920 U.S. Open by one stroke while working at the Town & Country Club in St. Paul, Minnesota. He went on to win the Senior PGA Championship in 1941. His son Jack Burke, Jr. won a PGA Championship and a Masters Tournament.

In the early days of the PGA Tour Milton Hershey was making money selling chocolate, and was also a golfer who owned the Hershey CC. In 1933 he held the first Hershey Open at his course, which offered a purse of $1,500. The Hershey Open continued for the next four years, but in 1938 Mr. Hershey changed the format. He had his professional, Henry Picard, invite 16 golf professionals for a “round-robin” event composed of eight two-man teams. It was seven 18-hole rounds, with each team playing a match against the other seven teams, one by one. All of the 16 invited professionals had wins on the PGA Tour except one, Ben Hogan. Mr. Hershey questioned Picard about inviting Hogan. Even though Hogan hadn’t won anything yet, Picard replied that he thought Hogan was going to be a great player.

In the early days of the PGA Tour Milton Hershey was making money selling chocolate, and was also a golfer who owned the Hershey CC. In 1933 he held the first Hershey Open at his course, which offered a purse of $1,500. The Hershey Open continued for the next four years, but in 1938 Mr. Hershey changed the format. He had his professional, Henry Picard, invite 16 golf professionals for a “round-robin” event composed of eight two-man teams. It was seven 18-hole rounds, with each team playing a match against the other seven teams, one by one. All of the 16 invited professionals had wins on the PGA Tour except one, Ben Hogan. Mr. Hershey questioned Picard about inviting Hogan. Even though Hogan hadn’t won anything yet, Picard replied that he thought Hogan was going to be a great player.

The Ram Golf Company was the first to embrace Braly’s idea. Ram Golf salesman, Brian Doyle, recruited Tom Robertson, who was one of the best ball strikers in the Philadelphia PGA as a test pilot for the FM shaft. Braly was able to tell right away which shaft was the right one for Tom and whether his FM idea was any good. With the FM shafts in his bag Robertson qualified for the 1983 PGA Championship and the PGA of America Cup team for club professionals that traveled to Scotland to take on the British PGA club pros.

The Ram Golf Company was the first to embrace Braly’s idea. Ram Golf salesman, Brian Doyle, recruited Tom Robertson, who was one of the best ball strikers in the Philadelphia PGA as a test pilot for the FM shaft. Braly was able to tell right away which shaft was the right one for Tom and whether his FM idea was any good. With the FM shafts in his bag Robertson qualified for the 1983 PGA Championship and the PGA of America Cup team for club professionals that traveled to Scotland to take on the British PGA club pros.

When Dougherty returned home as a civilian in 1969 a friend took him to Edgmont Country Club for a round of golf. Tiny Pedone, the golf professional and part owner, watched Ed hit a few golf balls and offered him a job running the practice range. A year later, through a Philadelphia connection, Ed landed a winter job at a golf course on St. Croix in the Virgin Islands working for golf professional Mike Reynolds. He was now able to work on his game 12 months a year. Under the tutelage of Reynolds, who had grown up playing golf at The Springhaven Club, Ed’s golf improved immensely.

When Dougherty returned home as a civilian in 1969 a friend took him to Edgmont Country Club for a round of golf. Tiny Pedone, the golf professional and part owner, watched Ed hit a few golf balls and offered him a job running the practice range. A year later, through a Philadelphia connection, Ed landed a winter job at a golf course on St. Croix in the Virgin Islands working for golf professional Mike Reynolds. He was now able to work on his game 12 months a year. Under the tutelage of Reynolds, who had grown up playing golf at The Springhaven Club, Ed’s golf improved immensely.

Oliver and five other players, all professionals, picked up their scorecards and teed off. Oliver was in the second group. After Oliver’s group had played their tee shots, someone mentioned that they might be pushing it by teeing off early. With that Oliver’s group waited until it was their time to begin their rounds before leaving the tee.

Oliver and five other players, all professionals, picked up their scorecards and teed off. Oliver was in the second group. After Oliver’s group had played their tee shots, someone mentioned that they might be pushing it by teeing off early. With that Oliver’s group waited until it was their time to begin their rounds before leaving the tee.

At that same time Max Cross was on the 18th hole at SDGC. As he was playing his second shot to the green with an iron, he was also struck by lightning. Cross was carried into the clubhouse unconscious. He was revived and returned to the 18th green where he had an eight-foot putt for a birdie. If he made the birdie putt he would qualify, and if he two-putted he would be in a playoff for the last four spots, but he took three putts. Ironically he was the professional at the Philadelphia Electric Company’s McCall Field Golf Course.

At that same time Max Cross was on the 18th hole at SDGC. As he was playing his second shot to the green with an iron, he was also struck by lightning. Cross was carried into the clubhouse unconscious. He was revived and returned to the 18th green where he had an eight-foot putt for a birdie. If he made the birdie putt he would qualify, and if he two-putted he would be in a playoff for the last four spots, but he took three putts. Ironically he was the professional at the Philadelphia Electric Company’s McCall Field Golf Course.

One of those was Felix Serafin, the head professional at the Country Club of Scranton. Serafin was in the fourth pairing of the day at 12:45. With a field of only 44 players the first starting time was 12:30.

One of those was Felix Serafin, the head professional at the Country Club of Scranton. Serafin was in the fourth pairing of the day at 12:45. With a field of only 44 players the first starting time was 12:30.

In January 1946 Ed Dudley, the president of the PGA of America and the pro at the Augusta National Golf Club, received a letter from the United States Golf Association informing the PGA that is was time to begin playing by the “Rules of Golf” again. Dudley fired a letter back stating that his organization had no apology to make. He stated that the PGA ran over 40 tournaments a year on the PGA Tour in all kinds of weather and course conditions. He also pointed out that the USGA only sponsored one tournament a year in which professionals compete and that was in the summer under favorable conditions.

In January 1946 Ed Dudley, the president of the PGA of America and the pro at the Augusta National Golf Club, received a letter from the United States Golf Association informing the PGA that is was time to begin playing by the “Rules of Golf” again. Dudley fired a letter back stating that his organization had no apology to make. He stated that the PGA ran over 40 tournaments a year on the PGA Tour in all kinds of weather and course conditions. He also pointed out that the USGA only sponsored one tournament a year in which professionals compete and that was in the summer under favorable conditions.