“Did You Know”

It took thirteen days for Sam Snead to win the L.A. Open over Ben Hogan!

It was late 1949. The PGA Tour would soon be kicking off a new year in January with the 24th annual Los Angeles Open at the 7,020-yard Riviera Country Club. With prize money of $15,000, only two tournaments offered larger purses that year-the PGA Championship and World Championship of Golf at Tam O’Shanter in Chicago.

Ben Hogan, who had won the 1948 US Open and the L.A. Open three times, all at Riviera CC, was home in Fort Worth, Texas recovering from a nearly fatal automobile accident. Even though his doctors had expressed doubt as to whether Hogan would play golf again, late in the year there was word “on the street” that Hogan had played a few holes.

On December 11 a Fort Worth newspaper reported that Hogan had been at Colonial CC and played 18 holes for the first time in ten months. Not walking, he rode a motor scooter. Hogan would only say “I didn’t hit them very well.” On December 15 the Los Angeles Junior Chamber of Commerce, sponsor of the L.A. Open, announced that it had invited Hogan to come to Los Angeles and referee the tournament.

Hogan walked 18 holes on December 20. He said, “I’m a mighty lucky guy.” Now weighing 155 pounds, which was 15 more than usual, he said he needed to lose some weight, which was something new for him. He said he might go to California to watch the L.A. Open and Bing Crosby tournament to get out of the bad weather in Fort Worth. Hogan said he thought he might be able to play some PGA Tour tournaments again sometime, but never 36 holes in one day. Hogan said one thing was sure he was not going to enter tournaments and shoot in the eighties.

The Hogans boarded a train for Los Angeles on December 28. Hogan filed his entry for the L.A. Open on Friday December 30, the last day to enter. The entry fee was $15, $1 for every $1,000 in the purse.

For six straight days Hogan played Riviera CC before taking Thursday off. At one point he said he was surprised by how well he was playing. The L.A. Open was scheduled to begin on Friday, January 6-with a Monday finish. 125 players would be in the starting field. Fifty were exempt, with 350 more golfers competing on Tuesday in 36-hole sessions at eight golf courses for the other 75 spots.

When the tournament began Hogan demanded that photographers not be allowed to take pictures of him during the round. He said cameras made him jumpy. Hogan felt that due to the circumstances more photographers would be following him than all the other players. The cameramen objected strenuously. Later Hogan agreed to be photographed, but only when he wasn’t playing a shot, which the photographers considered a ridicules request. A sign “No Cameras Please” traveled the golf course with Hogan.

When the tournament began Hogan demanded that photographers not be allowed to take pictures of him during the round. He said cameras made him jumpy. Hogan felt that due to the circumstances more photographers would be following him than all the other players. The cameramen objected strenuously. Later Hogan agreed to be photographed, but only when he wasn’t playing a shot, which the photographers considered a ridicules request. A sign “No Cameras Please” traveled the golf course with Hogan.

On Friday the starter on the first tee introduced Hogan from Fort Worth, Texas. Hogan interrupted the starter, saying I’m from Hershey, Pennsylvania. Ed Furgol, who had to qualify on Tuesday, took the first-round lead with a 68. Hogan was around in 73 strokes. On Saturday Jerry Barber (69-68=137), who had also qualified on Tuesday, took a two-stroke lead over the rest of the field. Later that year Barber would win the Pennsylvania Open as the professional at the Cedarbrook Country Club near Philadelphia. Hogan, with a second round 69, was five back at 142.

Rain arrived on Sunday. As the day wore on conditions became so bad Hogan putted with his pitching wedge on one green. At one point Hogan said that he was crazy to be out there. Finally with Hogan on the 11th hole and facing a flooded fairway from a barranca filled with rainwater, someone was sent to the clubhouse for help. After a 20 minute wait an official arrived at the 11th hole and play was stopped. Some pros felt like the tournament, which was run by the L.A. Junior Chamber of Commerce rather than pay the PGA its $1,500 management fee, might have been handled better on Sunday. The consensus was that play should have been halted at noon rather than 4:15. Sam Snead, Cary Middlecoff and Jimmy Demaret had walked off the course before play was stopped. Snead said that the Junior Chamber of Commerce could jump in the lake that used to be a golf course. All scores for the day were wiped so any disqualifying of Snead, Middlecoff and Demaret was negated as well.

Teeing off earlier than many of the leaders, Jerry Barber had posted a 73, while missing the worst of the bad conditions. At three under par 210, he would have had an insurmountable lead going into the last round. Hogan, who was doing the best of the other leaders, was four over par. With no gallery ropes along the fairways in those days, the leaders were spread out through the starting times for spectator management.

On Monday Barber tacked on a 72, to maintain his lead at 209, but Hogan was only two strokes back after a second consecutive 69. Barber fell away on Tuesday, while Hogan put together a third 69 for 280, which looked like the winning score. But the tournament wasn’t over. Sam Snead, playing six holes behind Hogan, was going low. At three under par for the day Snead needed two birdies to catch Hogan. With a chip and a 12-foot putt, Snead birdied the par five 17th hole, to get one of his needed birdies. His second shot on 18 finished 16 feet above and to the left of the hole. From there Snead put the Hogan victory party on hold by holing the putt for a 66, which put him in a tie with Hogan at 280.

In the locker room Hogan could hear the roar of the crown at the 18th green. He said Snead deserved to win and he wished Snead had. After five days of tournament golf his legs were tired. The Chamber of Commerce announced that an 18-hole playoff would be held the next day.

Dr. Cary Middlecoff, the golfing dentist, who said he knew something about medicine, called Hogan’s golf a near miracle.

On Wednesday rain returned to the usually sunny southern California. Fifteen minutes before play was to begin, the playoff was called off at the behest of Snead and Hogan and rescheduled for the next Wednesday. Hogan said, maybe they should play in Texas where it never rains.

From there Hogan and Snead left for Pebble Beach and the three-day Crosby Pro-Am. Snead finished in a 4-way tie for first at 214. There was no playoff. Hogan played and took 223 stokes, tying for 20th and out of the money.

On Tuesday Hogan played a practice round at Riviera CC while Snead was playing Lakewood Country Club in preparation for the Long Beach Open, which was starting on Thursday.

On Wednesday January 18, twelve days after they teed off in the first round, Hogan and Snead played off for the L.A. title. Snead won the playoff, with a 72 against a 76 for Hogan. Snead received a check for $2,600 while Hogan was picking up $1,900. Along with that Snead and Hogan shared 50 percent of the playoff receipts garnered from the 7,500 spectators. The playoff was broadcast stroke-by-stroke across the country on radio. Thirty minutes was aired on television that evening and sold to stations throughout the country.

Hogan skipped Long Beach where he was the defending champion. Then he played at Phoenix where the tournament had been renamed the Ben Hogan Open for that year. Demaret won while Hogan tied for 20th, winning last money. Hogan didn’t enter another tournament until the Masters in April where he finished tied for fourth.

Later in the year Hogan won the US Open at Merion Golf Club with its 36-hole Saturday finish and then an 18-hole playoff the next day, 90 holes in four days.

Much to the bewilderment of Snead, in December Hogan was voted the PGA Player of the Year, even though Hogan won two times while Snead was winning eleven times. Other than the US Open, Hogan won Sam Snead’s tournament at the Greenbrier Resort. Of the 173 sportswriters and broadcasters voting, Hogan received 112 of the votes.

Three homebred American professionals–Johnny McDermott, Tom McNamara and Mike Brady, were selected, with one more to be decided. While there, they would play in The Open before heading to France for the challenge match. Later, Alex Smith, a transplanted Scottish professional who was the professional at Wykagyl CC in Westchester County, New York, was chosen to fill out the four-man team. McDermott and Smith had won the last three US Opens.

Three homebred American professionals–Johnny McDermott, Tom McNamara and Mike Brady, were selected, with one more to be decided. While there, they would play in The Open before heading to France for the challenge match. Later, Alex Smith, a transplanted Scottish professional who was the professional at Wykagyl CC in Westchester County, New York, was chosen to fill out the four-man team. McDermott and Smith had won the last three US Opens.  The Open was played at Royal Liverpool Golf Club with 36 holes a day for two days. On Sunday, the day before the start of the competition, the golf course was closed to all play. The weather had been unusually hot and the forecast was good. Then during the tournament on Monday and Tuesday, June 23 and 24, the weather was about as bad as it could be. On the first day the greens were flooded from rain that began during the night and continued throughout the day. The second day presented gale force winds and drenching rain at times. McDermott had his moments. An opening round 75 was just two strokes off the lead, but an afternoon 80 set him back. On the second day McDermott was one under fours for the first seven holes and after nine holes only three strokes off the lead. But, with problems on the second nine his total for the round was 77. With a final round 83 McDermott tied for fifth, winning seven pounds and ten shillings. With a compact swing, J.H. Taylor had the right golf game for the elements. His 304 total made him the winner of The Open for a fifth time, this one by eight strokes. But, if not for having holed a six-foot putt on the final green of qualifying, Taylor would not have even been in the tournament.

The Open was played at Royal Liverpool Golf Club with 36 holes a day for two days. On Sunday, the day before the start of the competition, the golf course was closed to all play. The weather had been unusually hot and the forecast was good. Then during the tournament on Monday and Tuesday, June 23 and 24, the weather was about as bad as it could be. On the first day the greens were flooded from rain that began during the night and continued throughout the day. The second day presented gale force winds and drenching rain at times. McDermott had his moments. An opening round 75 was just two strokes off the lead, but an afternoon 80 set him back. On the second day McDermott was one under fours for the first seven holes and after nine holes only three strokes off the lead. But, with problems on the second nine his total for the round was 77. With a final round 83 McDermott tied for fifth, winning seven pounds and ten shillings. With a compact swing, J.H. Taylor had the right golf game for the elements. His 304 total made him the winner of The Open for a fifth time, this one by eight strokes. But, if not for having holed a six-foot putt on the final green of qualifying, Taylor would not have even been in the tournament.

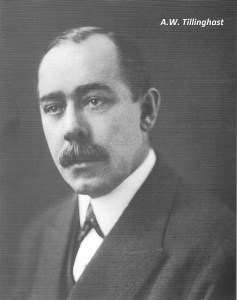

In order not to tarnish their amateur status, golf course architects like Philadelphia’s A.W. Tillinghast, George Thomas and Hugh Wilson had been wary of accepting compensation for their work.

In order not to tarnish their amateur status, golf course architects like Philadelphia’s A.W. Tillinghast, George Thomas and Hugh Wilson had been wary of accepting compensation for their work. The 1919 Pennsylvania Open was at Whitemarsh Valley Country Club. Before John Beadle teed off his amateur standing was questioned. Someone had said that Beadle, a former caddy at Llanerch CC, who was now 19, had caddied after the age of 16. Beadle finished second to Charlie Hoffner in the PA Open that day. The real crux of Beadle’s amateur status was that he was also entered in the Pennsylvania Amateur Championship, beginning the next day at that same course, Whitemarsh Valley. Beadle produced a letter verifying that his last caddy days were before his 16th birthday. But, with all of the conversation about his amateur status, Beadle did not play well in the PA Amateur. He would go on to be the professional at Paxon Hollow Country Club (later White Manor GC) for 35 years.

The 1919 Pennsylvania Open was at Whitemarsh Valley Country Club. Before John Beadle teed off his amateur standing was questioned. Someone had said that Beadle, a former caddy at Llanerch CC, who was now 19, had caddied after the age of 16. Beadle finished second to Charlie Hoffner in the PA Open that day. The real crux of Beadle’s amateur status was that he was also entered in the Pennsylvania Amateur Championship, beginning the next day at that same course, Whitemarsh Valley. Beadle produced a letter verifying that his last caddy days were before his 16th birthday. But, with all of the conversation about his amateur status, Beadle did not play well in the PA Amateur. He would go on to be the professional at Paxon Hollow Country Club (later White Manor GC) for 35 years.

The 1924 Shawnee Open kicked off three days after the Metropolitan Open ended in New York. Again, it was scheduled for 72 holes in two days. The players got a break as the high temperature in the Poconos for the two days was in the low 70’s. In a tightly contested tournament, Joe Kirkwood, who was living in Glenside, Pennsylvania and a member at Cedarbrook Country Club, led the first day, at 143. The second day Detroit’s Leo Diegel and Chicago’s Willie Macfarlane ended up in a tie for first at nine under par 287. As in 1923, the tournament officials sent them back out for an 18-hole playoff. Macfarlane said it wasn’t fair as Diegel was the best twilight golfer in the world. That seemed to be the case. With the sun sinking fast, Diegel put together a 69, which equaled the low round of the tournament, against a 76 for Macfarlane. Kirkwood finished third, one stroke out of the playoff. First prize was $500. In the late 1920s Diegel won the PGA Championship two years in a row, and later was the professional at Philmont Country Club.

The 1924 Shawnee Open kicked off three days after the Metropolitan Open ended in New York. Again, it was scheduled for 72 holes in two days. The players got a break as the high temperature in the Poconos for the two days was in the low 70’s. In a tightly contested tournament, Joe Kirkwood, who was living in Glenside, Pennsylvania and a member at Cedarbrook Country Club, led the first day, at 143. The second day Detroit’s Leo Diegel and Chicago’s Willie Macfarlane ended up in a tie for first at nine under par 287. As in 1923, the tournament officials sent them back out for an 18-hole playoff. Macfarlane said it wasn’t fair as Diegel was the best twilight golfer in the world. That seemed to be the case. With the sun sinking fast, Diegel put together a 69, which equaled the low round of the tournament, against a 76 for Macfarlane. Kirkwood finished third, one stroke out of the playoff. First prize was $500. In the late 1920s Diegel won the PGA Championship two years in a row, and later was the professional at Philmont Country Club.